Welcome to another edition on Random Walk Theory. In today’s post we will be focusing on South Africa’s latest Medium Term Budget. We will have a look at what has occurred over the past year, what kind of policies and plans have been put in place for our recovery and some interesting charts that show where South Africa stands relative to global peers.

Firstly, I believe that the budget was positive in a sense that all our cards are out on the table. We acknowledge that South Africa is facing a bit of a constraint when it comes to our Government’s ability to tackle any more economic downturns in future. With a constrained budget, increasing debt service costs and low economic growth, South Africa’s debt dynamics do not seem favorable at all. What is positive is the understanding by Treasury that the economy as a whole will need some serious reform in order to get ourselves out of this structural issue. Once again, open and honest conclusions which I believe would benefit South Africa in the medium to long term.

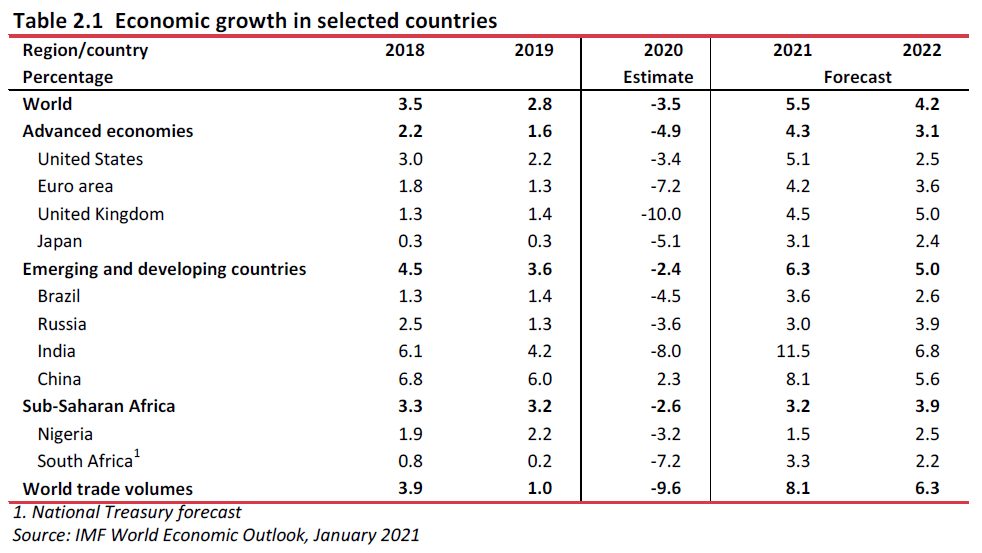

Beginning with global growth projections, we can see that South Africa is not expected to grow at a fast pace. This highlights some of the structural issues that are currently holding us back. With high interest rates and very low GDP growth, South Africa faces the challenge of having to find a balance of growing its capital expenditure whilst also being fiscally conservative, a mix that is difficult to achieve by any stretch of the imagination. We are predicted to have lower growth going forward than a lot of Developed Market countries which is alarming as we should be growing at a faster pace than those economies. The table below highlights this very issue.

Now to dive into some of the numbers and facts:

- The debt figures continue to rise, but the picture has improved somewhat.

- There appears to be a bigger focus on Capital Expenditure, which is positive for long term economic growth and capacity building.

- The budget deficit has been revised to 14 per cent of GDP in 2020/21 in response to the spending and economic pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, Gross debt has increased from 65.6 per cent to 80.3 per cent of GDP for the year 2020/21.

- The 2021 Budget proposes measures to narrow the main budget primary deficit from 7.5 per cent of GDP in the current year to 0.8 per cent in 2023/24

- The proposed fiscal framework will stabilize debt at 88.9 per cent of GDP in 2025/26. This is slightly better than what was expected back in October 2020 MTBPS.

- Government will roll out a free mass COVID-19 vaccination campaign for which R9 billion has been allocated in the medium term. This should be positive for the economy in the medium term as it reduces the need for further lockdowns if a large % of the population remains immune to the Covid strain. Where the risks lie are in the execution of a successful inoculation drive across the country.

- To support economic recovery, government will not raise any additional tax revenue in this budget. .

- Gross tax revenue for 2020/21 is expected to be R213.2 billion lower than projections in the 2020 Budget. However, due to a recovery in consumption and wages in recent months, and mining sector tax receipts, 2020/21 revenue collections are expected to be R99.6 billion higher than estimated in the 2020 MTBPS.

- As a result, government will not introduce measures to increase tax revenue in this Budget, and previously announced increases amounting to R40 billion over the next four years will be withdrawn.

- The main tax proposals include an above-inflation increase in personal income tax brackets and rebates, and an 8 per cent increase in alcohol and tobacco excise duties.

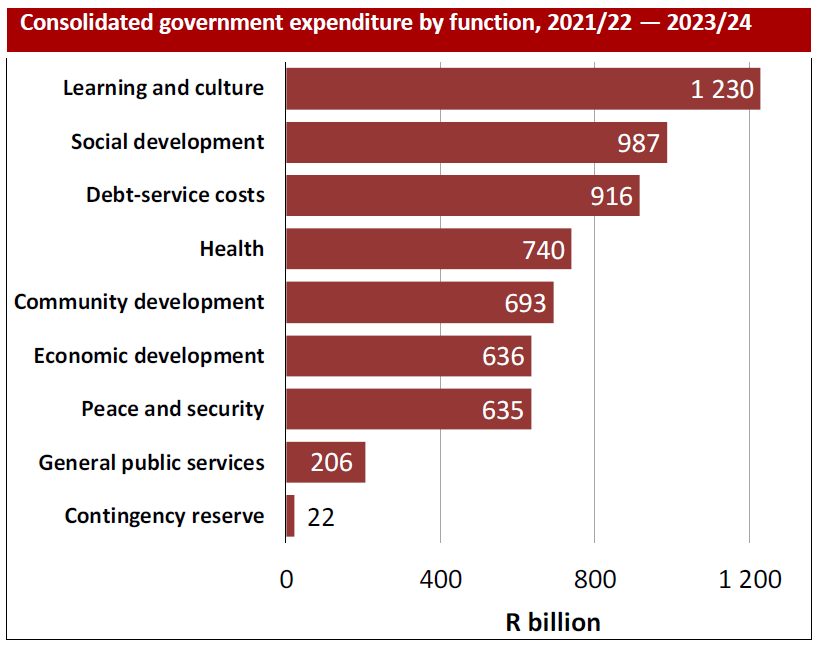

The fiscal position, which was already weak before the current crisis, has deteriorated sharply, requiring urgent steps to avoid a debt spiral. For several years, increasing debt-service costs have exceeded nominal GDP growth – a trend expected to continue over the medium term. The rate at which our interest expenses have increased has now created a large portion of our annual budget being spent on interest payments as opposed to increasing spending on either more capital goods (roads, infrastructure etc) or increasing spending on social services (education, safety, health)

If this does not change, the economy will not be able to generate sufficient revenue for the state to service debt. Over the medium term, debt-service costs are expected to average 20.9 per cent of gross tax revenue. This has been noted as a bad structural feature in our budget over the past few years and leaves us in a potentially tight spot. Debt-service costs will rise from R232.9 billion in 2020/21 to R338.6 billion in 2023/24. These costs, which were already the fastest-rising item of spending, now consume 19.2 per cent of tax revenue. Funds that could be spent on economic and social priorities are being redirected to pay local and overseas bondholders. Over the next three years, annual debt-service payments exceed government spending on most functions, including health, economic services, and peace and security.

To give a bit more color to the above situation, imagine that you earned R100.00 a year and you needed to allocate the R100.00 to all your expenditures. Now assume that you have some debt that needs to be paid off in a couple of years, and that you are currently being charged R10.00 interest a year. Therefore 10% of your salary is going towards interest payments (debt service costs) and the rest is split into other crucial expenses. Now, let’s imagine a situation where your interest costs increases due to interest rates rising, as well as the lender hiking your rates due to increased perceived risks (you’ve actually got more debt than you previously mentioned and you’ve started missing some payments). All of a sudden, you’re paying 20% of your income in interest payments and now have less money for the other crucial expenditures. Additionally, if you have emergency and need to further take on more debt, you’re less likely to be able to afford it over the long term and still maintain the amount of the stuff you need to spend on. Eventually you’ll need to reduce your spending on the other crucial expenditures as more of your income gets taken over by debt servicing costs. Either your debt needs to be consolidated or you need to make more money to be able to afford the current level of consumption + interest payments. This is essentially the situation Government is in right now.

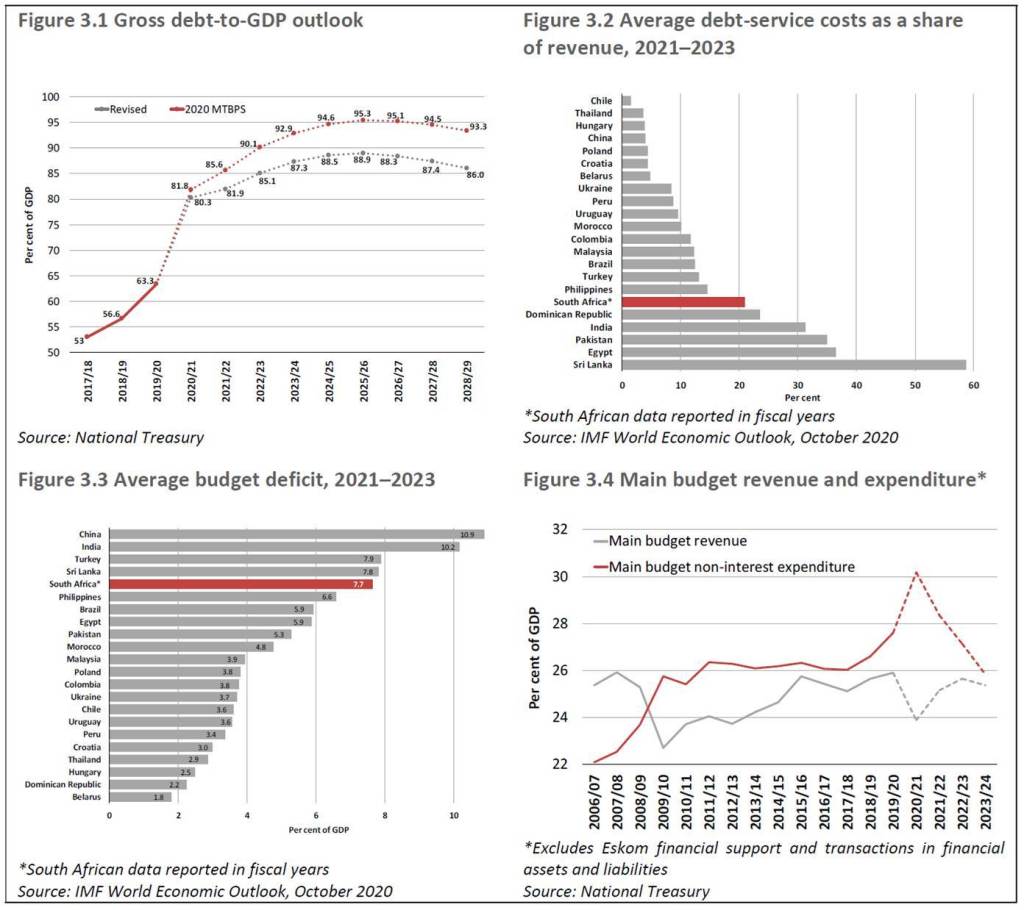

The graph below highlights where South Africa stands in terms of the current debt dynamics. Figure 3.1 highlights the slight improvement in our debt dynamics relative to what was projected in the 2020 MTBPS. We still have experienced a big spike in debt, but the rate of increase is expected to slow down as well as the absolute level (grey line lies lower than the red line). Figure 3.2 also highlights that we are part of a group of countries that have a large sare of the Government’s revenue being eaten up by debt service costs. The highlights that the interest rates we are paying on our debt is not sustainable, given our level of growth. figure 3.3 also highlights that we are set to have one of the wider budget deficits when compared to other peers. Again, not good given that this debt will continuously need to be serviced over time, and gives us less room to spend on other essential services.

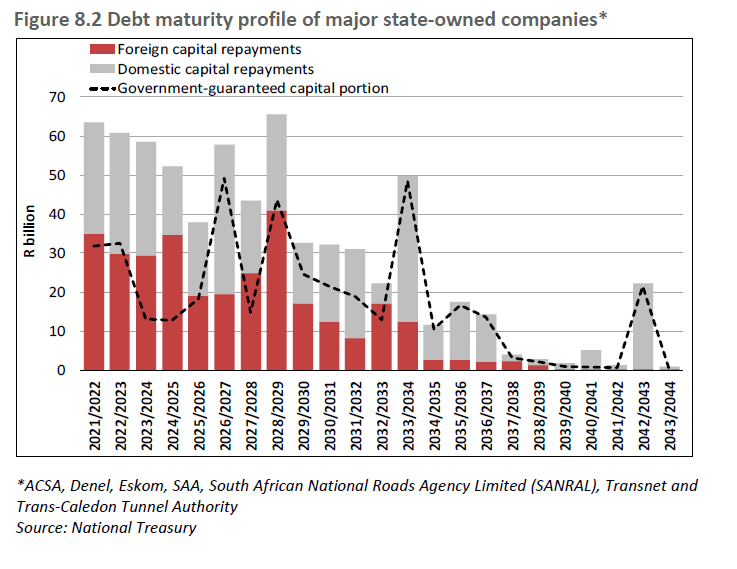

Having a look at the other issue South Africa is faced with, the medium-term debt redemptions of state-owned companies total R182.8 billion. Without rapid improvements in financial management and the resolution of longstanding policy disputes – including the user pay principle – they will continue to put pressure on public finances. If these entities cannot support themselves and pay off their debt, then the Government will have to step in and add more capital into these business that aren’t doing well.

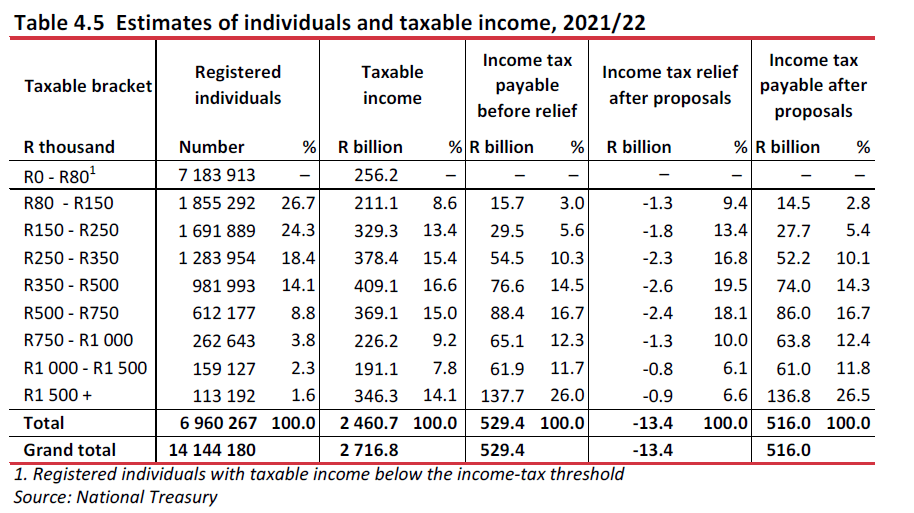

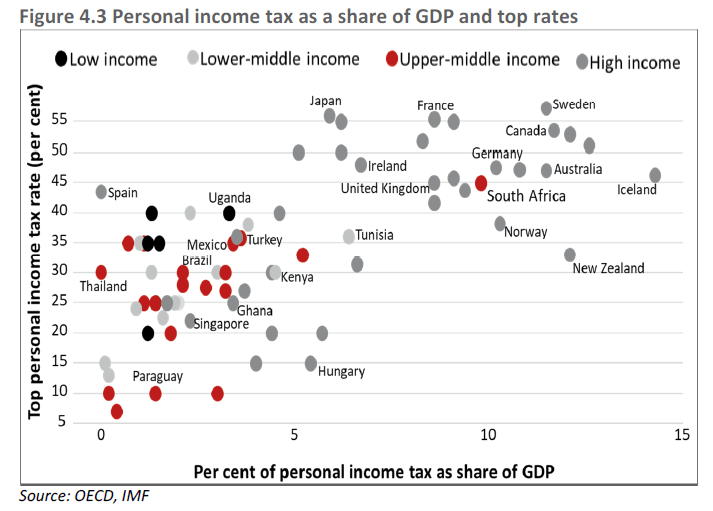

This is not feasible in the long term in my view given the constraint on the tax base. South Africans are already paying a a large share of their incomes to taxes, even by global standards. Relative to our economic wealth, South Africans pay a large share of their income in the form of taxes and compares closely to many “well off” countries, even though their citizens are much wealthier than ours. Expecting already constrained consumers to pay more is not a viable option without growth. We already have a small portion of the population contributing to Personal Income tax (about 7million people actively pay Personal Income tax vs a population of about 60 million) and the political will to hike VAT rates is low given how sensitive the majority of the country is to changes in VAT.

The image below shows South Africa relative to other countries globally. The horizontal axis represents the amount of personal income tax as a % of GDP. The vertical axis shows each country’s highest Personal Income Tax (PIT) rate. South Africa currently lies in the top right hand corner of the chart, highlighting that we have a high top PIT tax rate as well as high overall average taxes. The mismatch is clear given that this region is mostly associated with richer countries whilst peers who are similar to us have much lower PIT tax as a % of GDP and lower top tax rates.

·

In summary, it appears that South Africa will either need to get growth up or consolidate on its expenditure, which is a very difficult thing to do. We cannot forget that South Africa has a large portion of people currently employed by the state and any shedding of those jobs will be bad for consumption everywhere in the country. This is highlighted in the budget and the acknowledgement of how difficult consolidation will be leaves mes me to believe that the focus should be on growth enhancing policies without breaking line on the expenditure side. This will need capital to be “crowed in” or rather, Government will need to allow investors to take some of the risks themselves and take away some expenditures and costs the government currently has on its plate. Privatization could be one avenue for some state assets but allowing some blended mix of financing for future projects can allow Government to bear less of the risks whilst being able to consolidate on its expenditures.

After all, that is the point of capital markets in my view; it’s a place where you can find players (investors) who are willing to take on and fund risky projects, or a portion of it, for a particular price. If government allows private participation in certain projects, it allows some of the risk to be held by people who are willing to take on the risk.

Hope this note was insightful and has given some interesting perspectives on the Budget.

Until next time.

Thomo.